Electrical resistance within speakers, amplifiers, as well as all basic electrical connections, is expressed in ohms, named after George Simon Ohm, a German physicist. While we needn’t go into the background of him and his achievements, or even the heavy details about resistance, ohms, or impedance, this is an area that is often confusing to people. The following is a primer all about ohms and how it relates to speakers and amplifiers. My hope is that very simply, any confusion on the topic will be eliminated.

Some of the Usual Questions

When running one cabinet, for example a standard Marshall 4 x 12 cabinet at 16 ohms, it is easy to presume and know that the amplifier head should also be set to 16 ohms for best performance. However, in other situations, other questions can and do pop up. What if you don’t have a 16 ohm output for the cabinet and the head you’re using only has options for 8 or 4 ohms? Can it still be run safely? What about the case of using a 4 ohm cabinet but the amp only has settings for 8 or 16 ohms? And what about running more than one cabinet – what setting should the amplifier’s ohms adjustment be set to then? What if you have two cabinets with different ratings, say one 8 ohm and one 16 ohm? Can they be run together safely and if so, again, what do you set the ohms selector on the head to?

Fortunately, the principles about ohms aren’t too complex in terms of what musicians need to know. For those interested in knowing more, I’d suggest any basic electronics book that defines the terms conductance, resistance, amperes, and volts since these are all related. In addition, Ohm’s Law is a fundamental law in electronics, but again, it’s not important if you are, like most musicians, only interested in understanding the answers to the questions presented above. If you fall into this group, then what we need to talk about are the different ways to make connections and how they work.

Parallel and Series

Electronics work on positive (a.k.a. “hot”) and negative (a.k.a. ground) forces. As such, single-voice coil speakers each have a positive and negative terminal; the cable that plugs into a cabinet also uses a positive and negative connection; the jacks that are on the amplifier also have individual positive and negative connections. The circuitry running within the amplifier has various positive and negative connections. I’m not trying to sound redundant, but it is important to understand this simple idea.

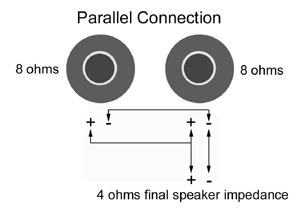

Now, if we take a single 8 ohm speaker and attach it to another 8 ohm speaker, we can actually hook it up so that its resistance in ohms can be one of two ratings. If we wire the positive and negative terminals of each speaker together, this is called a parallel connection. Parallel connections reduce overall resistance, and as such the ohm’s rating would be halved to four ohms. What if we add another pair of 8 ohm speakers to the first pair and wire them all together the same way? The second pair of 8 ohm speakers would be of course halved to four ohms. Then, when we wire the resulting two 4 ohm pairs together, this would of course bring the overall final resistance to 2 ohms.

Now, if we take a single 8 ohm speaker and attach it to another 8 ohm speaker, we can actually hook it up so that its resistance in ohms can be one of two ratings. If we wire the positive and negative terminals of each speaker together, this is called a parallel connection. Parallel connections reduce overall resistance, and as such the ohm’s rating would be halved to four ohms. What if we add another pair of 8 ohm speakers to the first pair and wire them all together the same way? The second pair of 8 ohm speakers would be of course halved to four ohms. Then, when we wire the resulting two 4 ohm pairs together, this would of course bring the overall final resistance to 2 ohms.

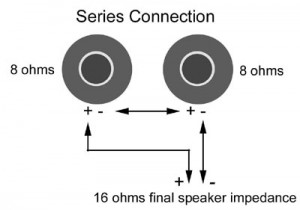

Now what about that “other” way to wire the original pair of 8 ohm speakers to get a different resistance rating? If we take the negative terminal of the first speaker and run it to the positive terminal of the second speaker, then use the positive of the first speaker and the negative of the second speaker as the primary connection back to the amplifier, we’ve then created a series connection. Series increases overall resistance and so our ohms rating when both 8 ohm speakers are run in this fashion is doubled to 16 ohms. If you add another pair of 8 ohm speakers in series to the series “chain”, you’ll effectively create a 32 ohm load.

Now what about that “other” way to wire the original pair of 8 ohm speakers to get a different resistance rating? If we take the negative terminal of the first speaker and run it to the positive terminal of the second speaker, then use the positive of the first speaker and the negative of the second speaker as the primary connection back to the amplifier, we’ve then created a series connection. Series increases overall resistance and so our ohms rating when both 8 ohm speakers are run in this fashion is doubled to 16 ohms. If you add another pair of 8 ohm speakers in series to the series “chain”, you’ll effectively create a 32 ohm load.

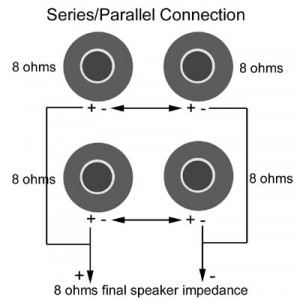

Typical Marshall cabinets run four 16 ohm speakers, so how can the overall resistance of the cabinet remain at 16 ohms using either series or parallel wiring? The answer is that it cannot, so a combination scheme called series/parallel is used. We can wire the four 16 ohm cabinets in different ways to get the same 16 ohm result using series/parallel. One way is to first wire each pair of 16 ohm speakers in series to create two 32 ohm pairs. Then, when we combine the two pairs together in parallel to create the final speaker load, a 16 ohm set results. Alternately, we can first wire each pair of 16 ohm speakers in parallel, and create two 8 ohm pairs. Then we can wire the two 8 ohm connections in series to again bring the overall impedance to 16 ohms. There is no “better” way to do the wiring in this instance, either method will produce the same result and sound the same. Take a look at the various diagrams to visually see how series, parallel, and series/parallel connections are made.

Typical Marshall cabinets run four 16 ohm speakers, so how can the overall resistance of the cabinet remain at 16 ohms using either series or parallel wiring? The answer is that it cannot, so a combination scheme called series/parallel is used. We can wire the four 16 ohm cabinets in different ways to get the same 16 ohm result using series/parallel. One way is to first wire each pair of 16 ohm speakers in series to create two 32 ohm pairs. Then, when we combine the two pairs together in parallel to create the final speaker load, a 16 ohm set results. Alternately, we can first wire each pair of 16 ohm speakers in parallel, and create two 8 ohm pairs. Then we can wire the two 8 ohm connections in series to again bring the overall impedance to 16 ohms. There is no “better” way to do the wiring in this instance, either method will produce the same result and sound the same. Take a look at the various diagrams to visually see how series, parallel, and series/parallel connections are made.

Added Facts About Series and Parallel Connections

When running anything in series (whether it is the light bulbs on a Christmas tree or speakers), if even one part of the chain fails or a single connection is lost, the entire chain itself will not function. This is important to consider when troubleshooting speakers or when building a system and deciding what types of speakers to use. All other things equal, if you are building a single cabinet for example with a pair of speakers that need to operate at 8 ohms, it is best to use two 16 ohm speakers wired in parallel, rather than two 4 ohm speakers run in series. If one of the speakers fails or a connection is lost in the parallel wired setup, the other speaker will continue to function. This will at least get you through the gig!

Ohms and Amplifiers

Guitar amplifiers that have multiple outputs use parallel wiring internally at their output jacks. Why you may ask? Well, for one reason, if they did not, then the outputs on the amp would only work if ALL outputs would be used of course! Remember again that a series connection needs to have all connections present to work and this would apply to an amplifier’s output jacks as well. So as a result of knowing that an amplifier’s speaker outputs are wired in parallel, running two 16 ohm cabinets in a standard Marshall amplifier head would result in an 8 ohm load and therefore the amplifier should be set at 8 ohms accordingly. Some older Marshalls had four speaker outputs. Using the same principles, four 16 ohm cabinets ran in parallel together would result in a 4 ohm load and you would then set the Marshall to operate at 4 ohms.

If we go back to some of the earlier questions, I hinted about situations that referred to impedance mis-matching. Recall the questions: “But what if you don’t have a 16 ohm output (for the speaker cabinet rated at 16 ohms) and the head only has options for 8 or 4 ohms? Can it still be run safely? What about the case of using a 4 ohm cabinet but the amp only has settings for 8 ohms or above?”

The answer to the first question regarding whether a 16 ohm cabinet can be run safely with an amp that has settings for 8 or 4 ohms is yes. However, when running the head at a lower ohm rating then the cabinet, the result will be a significant degree of power loss. In the second case of using a 4 ohm cabinet with an amp that must be run at 8 ohms, this will stress an amp and cause it to overheat. Technically, you’ll get more power output (not efficient or stable power output mind you!) to some degree, but again, at the expense of burning out a transformer and/or other components. Not a good idea!

One of the questions earlier speculated about the use of two different cabinets in a setup, one being an 8 ohm, the other a 16 ohm. For best performance, this is not recommended. However, if you insist on having to do this setup, just make sure that the amplifier impedance is lower than the combined 8 and 16 ohm parallel load. The formula for calculating the impedance when not using equivelant cabinets is different, i.e. the “halving” or “doubling” that is done to get ratings when using series and parallel won’t work.

We won’t bother with the mathematical formula used. Let me tell you the “easy” way to come up with the calculation. Using a calculator with a reciprical key (“1/x”), do this: enter the first resistance value (for our example, press 8 for our 8 ohms), then press the “1/x” key. Then press “+” and then enter the next resistance value (16) and again press the “1/x” key. Then press “=”, then “1/x” and you’ll have your final answer.

Based on this, the final resistance rating of the single 8 and 16 ohm cabinet ran in parallel is approximately 5.33 ohms. To run this setup reliably, but of course understanding that there will be some power loss, make sure the amplifier is set to 4 ohms. Better yet, sell one of the cabinets and purchase a new one with an appropriately matched ohms rating so you can get all the power out your amplifier and therefore have the tightest and most powerful sound available out of your rig. Hope all this helps!

Please correct me if I’m wrong here but, if you have the choice of running your ‘tube’ amp at 4 or 8 ohms into a 5.33 ohms cabinet, wouldn’t you want to set the amp to 8, rather than 4? Its always been my understanding that when faced with a choice of running a tube amp into a cabinet of more or less impedance, you should always choose the lower of the two. Tube amps do not like to see higher impedance. If they did, it would be okay to run a tube amp without a speaker connected. Which is basically an infinite (higher) impedance, and this is a no no when it comes to tube amps.

Or? Are you saying here that you should run the amp at 4 ohms because it is the closest to the 5.33 ohm mismatched impedance?

Thanks in advance-

-Jay

Keen to hear a response to Jay’s questions.

Also, I have assembled a tiny amplifier kit which I hope to run with my headphones that have an impedance of 32ohms. The kit instructions says it is designed for a 4 ohm loudspeaker (up to 9V), but can power a 8ohm loudspeaker if the input voltage is 6volts or less. Would this be because it might somehow damage the speaker? If so I still don’t understand how the higher an impedance, the more potential for damage. According to Ohm’s law, the less voltage applied to a specific resistance/impedance, the higher the current will be drawn by that component, resulting in more heat. Alternatively, the higher the ohms the less current drawn. Maybe there’s a basic principle in amp/speaker circuits I still don’t understand.

Cheers is advance.

It is better to set the amp at 4 ohms instead of 8 in the situation you present. In mismatching amps and cabinets, there are two tradeoffs. If you run a cabinet with a lower impedance than the amplifier, the net effect is a strain on the amplifier tubes and transformers. Think of it as “running them hotter” as more power is being forced out then what the amp is designed to do. In the opposite end (cabinet has higher impedance than the amplifier), the opposite occurs and there is a slight loss of power and efficiency as the tradeoff. ONLY in ‘extreme’ cases of mismatches with very low impedances and high impedances run together (say 2 ohms running to 32 ohms and vice versa), damage can occur to the amplifier for different reasons. In an “extreme” low amp/high speaker situation, an occurrence of what’s known as flyback voltages from the mismatch can damage the output transformer. In an “extreme” high amp/low speaker situation, you could theoretically damage the power transformer through overheating. In either case, one would hope that the fuse for the output transformer (high-tension or HT fuse in an amp) or the mains fuse would blow first. But these again are extreme conditions and tube amps are NOT as sensitive as solid state to mismatches generally. Mesa Boogie, among other companies have written about mismatches as well and also discuss the topic with recommendations that align with the article here.

I suspect that with the kit, the concern isn’t damage to the speaker when running at 8 ohms, but rather a loss of power and efficiency at the mismatch.